—

Al Hirschfeld's caricatures captured the vivid personalities of entertainers

and their performances for more than 75 years.

He drew a vast and imaginative portrait

of the performing artists of his lifetime, particularly in the theater.

He was a familiar figure at first nights and at rehearsals, where he had

perfected the technique of making a sketch in the dark, using a system

of shorthand notations that contributed to the finished product.

His art was compared by critics to that

of Daumier and Toulouse-Lautrec but, ultimately, it was Hirschfeld, cannily

perceptive, wittily amusing and benignly pointed.

Hirschfeld's art was distinguished by his

deep feeling for people. He never went for the jugular, except on one

occasion, when he did an ironic drawing of David Merrick, the producer,

as a demonic Santa Claus. Merrick, to Hirschfeld's mixed reaction, liked

the image so much that he bought it and used it on his Christmas cards.

Hirschfeld continued to work until his

death. On Saturday 18 January 2003, as usual, he was at work in his studio,

drawing the Marx brothers, all of whom were his friends.

In 1996 a film documentary of the artist's

life was made by Susan W. Dryfoos: The Line King.

Hirschfeld was best known for the caricatures

that appeared in the drama pages of The New York Times. But his

work also appeared in books and other publications and is in the collections

of many museums. His other artistic work often reflected his travels to

the South Pacific and to Japan, where he was deeply influenced by aesthetics

and techniques.

Hirschfeld's reinventions caught the spirit

of their subjects with lines that, studied individually, might seem irrelevant

but, taken together, added up to characteristic eyes, hairdos and motions

— all in such a way as to distill the character of his subject.

Dancer Ray

Bolger's portrait shows him as a bumbling magician dancer. Barbra

Streisand in “Funny Girl” looks birdlike, all points,

with wide-open mouth and lidded eyes. Zero

Mostel as Tevye in “Fiddler on the Roof” appears

as a circle of beard and hair with fierce eyes peering upward, as at a

heaven that did not understand.

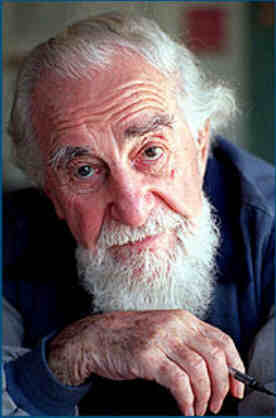

Hirschfeld was a lively, white-haired,

white-bearded man 1m73 tall, who saw himself this way: “A couple

of huge eyes and huge mattress of hair. Large eyes with superimposed eyebrows.

No forehead. The forehead that you see is just the hair disappearing.”

In the 1930's and 40's Hirschfeld wrote

pieces on comedians, actors, Greenwich Village and films for The NY

Times. In one he sharply criticized Snow White, Walt Disney's

animated movie, for imitating “pantographically” factual photography

and for being in the “oopsy-woopsy school of art practiced mostly

by etchers who portray dogs with cute sayings.”

Albert Hirschfeld was born in St. Louis, one of three sons of Isaac and

Rebecca Hirschfeld.

Albert Hirschfeld was born in St. Louis, one of three sons of Isaac and

Rebecca Hirschfeld.

When he was 12 years old and had already

started art lessons, the family moved to New York City. He attended public

schools and the Art Students League. By 18, he was art director for Selznick

Pictures. In 1924 he went to Paris where he continued his studies in painting,

sculpture and drawing.

It was during a trip to Bali — where the

intense sun bleached out all color and reduced people to “walking

line drawings”, as he later recalled — that he became “enchanted

with line” and concentrated on that technique.

While on a visit to New York in 1926 from

Paris, he went to the theater one evening with Richard Maney, a press

agent who was handling his first show, a production that starred Sacha

Guitry, the French star, in his first US performance. With a pencil, Hirschfeld

doodled a sketch in the dark on his program. Maney liked it and asked

Hirschfeld to repeat it on a clean piece of paper that could be placed

in a newspaper. It appeared on the front page of The New York Herald

Tribune, which gave him more assignments.

Some weeks later, the artist received a

telegram from Sam Zolotow of The NY Times's drama department

asking for a drawing of Harry Lauder, who was making one of his numerous

farewell appearances. Hirschfeld delivered it to the messenger desk at

the newspaper. A few weeks later, he had another assignment from The

NY Times.

This went on for about two years, he later

recalled, until he first met Zolotow in a theater lobby. He was told to

deliver his next drawing in person, and he did, making the acquaintance

of Brooks Atkinson, then The NY Times's drama critic, who became

a close friend. Hirschfeld was never a salaried employee of The NY

Times but worked on a freelance basis that left ownership of his

work in his hands after it had been published in the newspaper.

He applied his art to other subjects elsewhere.

In the 1920's and early 30's, imbued with a sense of social concern, Hirschfeld

did serious lithographs that appeared, for no fee, in The New Masses,

a Communist-line magazine. Eventually, he realized that the magazine's

interest was politics rather than art. After a dispute about a caricature

he had made of the Rev. Charles E. Coughlin, the right-wing, anti-Semitic

radio priest, the artist renounced a political approach to his work and,

in his The World of Hirschfeld, later wrote, "I have ever since

been closer to Groucho Marx than to Karl."

The Hirschfelds' daughter, Nina, was born

in 1945. On 05 November of that year, her name made its debut in the pages

of The NY Times, on an imagined poster in a circus scene for

a drawing about a new musical, Are You With It? Thereafter Nina's

name would covertly insinuated into a caricature one or several times

— perhaps in the fold of a dress, a kink of hair, the bend of an arm.

So popular did the Ninas become that the

military used them in the training of bomber pilots to spot targets. A

Pentagon consultant found them useful in the study of camouflage techniques.

Hirschfeld realized how addicted readers had become to Ninas when he purposely

omitted them one Sunday only to be besieged by complaints from frustrated

Nina hunters.

One Nina fan was Arthur Hays Sulzberger,

then the publisher of The NY Times. In 1960 he wrote a letter to Hirschfeld

to say that he always first looked for Ninas in Hirschfeld drawings but

had learned that each included more than one. “That really isn't

fair, since not knowing how many there are leaves one with a sense of

frustration,” Sulzberger wrote.

A letter from another reader suggested

that the artist note in the caricature how many times a Nina appeared.

From that time on, Hirschfeld appended the number of Ninas in the lower

right-hand corner of each drawing (omitted in lithographic reproductions).

Hirschfeld believed that acceptance of caricatures was a slow process

and one that was always difficult for the artist. Occasionally actors

and producers hinted at lawsuits or withdrawal of advertising because

they did not find his drawings sufficiently attractive.

But his art flourished and endured, and

it sometimes seemed as if there were Hirschfelds at every point of the

compass. He was represented for more than a quarter of a century by the

Margo

Feiden Galleries, which once estimated that there were more than 7000

Hirschfeld originals in existence. One that is no longer in existence

is a Hirschfeld self-portrait reproduced in paint on Madison Avenue between

62nd and 63rd Streets, in front of the gallery in 1994. It was 14.6 m

long, complete with Ninas, and survived a partial washout by rain the

first day.

In 1991 the United States Postal Service issued

Comedians

by Hirschfeld, a booklet of five 29-cent stamps honoring comedians

— Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy, Jack

Benny, Fanny Brice and Bud Abbott and Lou Costello — as designed by the

artist; contrary to post office policy forbidding secret marks, he was

allowed to insert his trademark Ninas into the depictions.

In the early 1940's he and a close friend,

the writer S. J. Perelman, collaborated on a musical with Ogden Nash and

Vernon Duke: Sweet Bye and Bye and opened and closed in Philadelphia

on the same night.

Subsequent travels resulted in books —

words by Perelman, pictures by Hirschfeld — like Westward Ha! or Around

the World in 80 Clichés and Swiss Family Perelman.

In 1995 appeared the CD-ROM, Hirschfeld:

The Great Entertainers.

Dolly Haas Hirschfeld was his 2nd wife,

adviser and social director from 1942 to her death 1994. An earlier marriage

to Florence Ruth Hobby ended in divorce. In 1996 he married Louise Kerz,

a research historian in the arts and a longtime friend, who survives him.

He is also survived by his daughter, Nina Hirschfeld West of Austin, Texas.

In something of a self-criticism, Hirschfeld,

in a letter to The NY Times in 1986, expressed his opinion about

an article in the Science section on defining beauty. “Beauty is

incapable of being defined scientifically or aesthetically. Anarchy takes

over. Having devoted a long life to the art of caricature I have rarely

convinced anyone that caricature and beauty are synonymous. Beauty may

be the limited proportions of a classic Greek sculptured figure but it

does not have to be — it could be an ashcan.”

— Author of The World of Hirschfeld (1970) —

Show Business Is No Business — The American Theater as Seen

by Hirschfeld — Hirschfeld on Line (1999) — Hirschfeld's

New York — Hirschfeld's Hollywood — The Speakeasies of 1932

— Hirschfeld's Harlem.

— Hirschfeld

Gallery

— Self

Portrait, Absolut — Self Portrait, Inkwell [>>>]

— Self

Portrait at 86 — Self

Portrait at 89 — Self

Portrait at 90 — Self

Portrait at 98 — Self Portrait at 99 [above, left, extra

hand added] — Self

Portrait in Barber's Chair — The

Artist with his wife Louise Strolling Through the World's Greatest City

— Houdini

(2002) — Bill

Gates (2000) — Puccini

(2000, 68x53cm) — Tchaikovsky

(1991) — Democratic

Presidential Candidates (1988) — The

Taj Mahal, A Tourist Eye's View (1947) — Alfred

Hitchcock