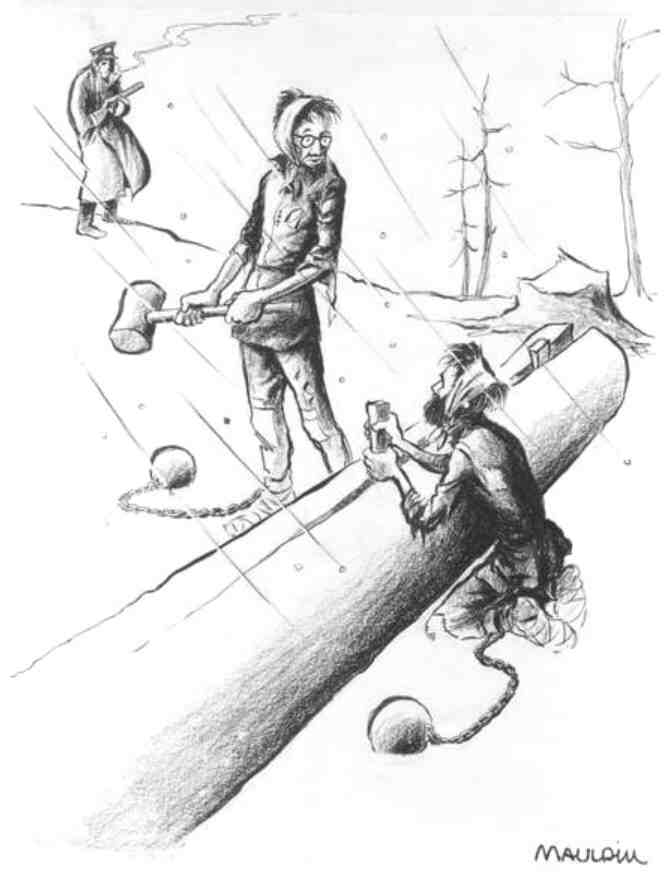

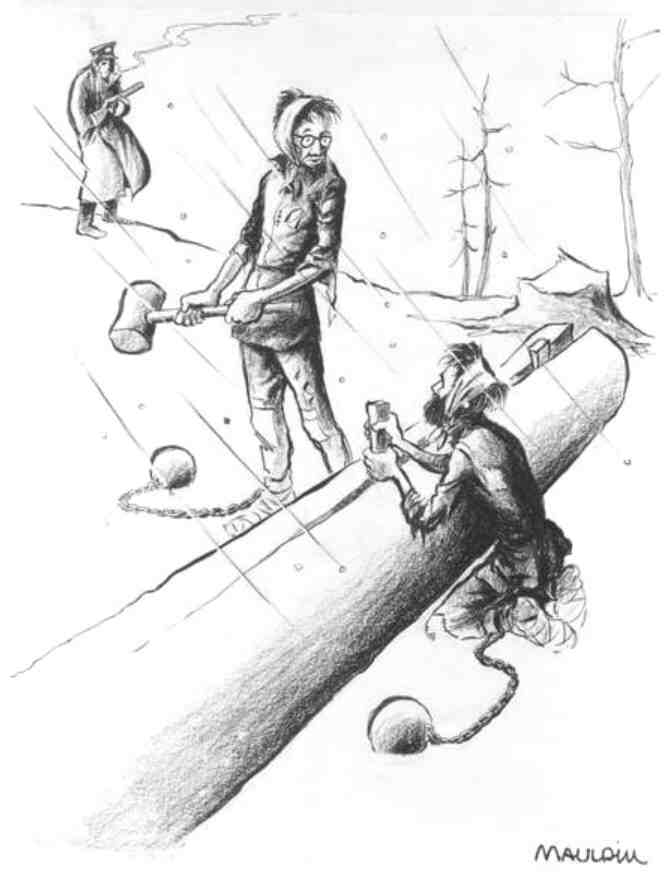

I

Won the Nobel Prize for Literature. What was your crime?

by Bill Mauldin, 1958

Bill Mauldin, the Army sergeant who created Willie

and Joe, the cartoon characters who became enduring symbols of the grimy, irrepressible

US infantrymen who triumphed over the German army and prevailed over their own

rear-echelon officers in World War II, died on 22 January 2003 in Newport Beach,

California. He was 81. The cause was pneumonia. Mauldin had been suffering from

Alzheimer's disease.

After Willie and Joe won the war, Mauldin became

a syndicated newspaper cartoonist and went on for more than 50 years to caricature

bigots, superpatriots, doctrinaire liberals and conservatives, and pompous souls

in whatever form they appeared. He won the Pulitzer Prize twice, once in 1944

for his World War II work, again in 1959 for his commentary on Soviet treatment

of Boris Pasternak [above]. Mauldin gave up regular cartooning assignments

in the early 1990's, complaining that arthritis made drawing too difficult.

He frequently lamented that editorial cartoonists

were too soft and that more of them needed to be "stirrer-uppers." Mauldin worked

full time at being a stirrer-upper, and while he was on duty nobody was safe

from his editorial brush. During the war, he excoriated self-important generals,

grassy green "90-day wonders," insensitive drill sergeants, palate-dulled mess

sergeants, glamor-dripping Air Force pilots in leather jackets, and café

owners in liberated countries who rewarded the thirsty G.I.'s who had freed

them by charging them double for brandy. He was nothing short of beloved by

his fellow enlisted men.

But no Mauldin characters were more memorable

than Willie and Joe, the unshaven, listless, dull-eyed, cynical dogfaces who

spent the war fighting the Germans, trying to keep dry and warm and flirting

with insubordination. They were the stars of Up Front Mauldin's wartime

best seller, and their exploits were reported regularly in various service publications,

including Stars and Stripes and the 45th Division News. Their

likenesses were found in pup tents and bivouacs from Brittany to Berlin, tacked

up next to the inevitable glossies of those other G.I. favorites, Betty Grable

and Dorothy Lamour. Mauldin began his sojourn with the 45th, which arrived in

North Africa and fought into Italy, but he sampled many divisions and places

as his fame grew.

Willie and Joe were the guys who always got sentry

duty when it rained or snowed and shrapnel in their backsides whenever they

left their foxholes. It was they who contended with lice and fleas, complained

constantly about the K rations they were supposed to eat, slept in rat-infested

barns, never seemed to find the soap when they had the rare opportunity to bathe,

and suffered the incessant, grinding, morale-destroying boredom that only the

infantry soldier knows.

The only thing that could never be questioned

about Willie and Joe was their determination to survive and win. Gen. Dwight

D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander, looked forward to their adventures,

and Gen. Mark Clark so appreciated them that he saw to it that Mauldin got a

specially equipped Jeep in Italy so that he could go where he wanted and draw

what he wished. Ernie Pyle, one of the G.I.'s favorite correspondents, termed

Mauldin the best cartoonist of the war because he drew pictures of the men who

were "doing the dying," even though nobody could ever kill Willie and Joe.

Gen. George S. Patton was one of a small minority

who had no use for them. He liked his heroes cleanshaven and obedient, and he

was uneasy that the men who served under him revered the likes of such unorthodoxy.

Asked toward the end of the war to comment on Sergeant Mauldin's cartoons, General

Patton replied, "I've seen only two of them, and I thought they were lousy."

Mauldin's representations have endured in unforgettable

images and words:

"Just gimme a coupla aspirin. I already got a Purple Heart," says a weary

Joe to a corpsman seated at a table containing medicine and medals.

"He's right Joe," says Willie after a superior admonishes them for the slovenly

way they look. "When we ain't fightin' we should ack like sojers."

"Must be a tough objective," says Willie to Joe as they huddle on the side

of a road, weapons ready. "Th' old man says we're gonna have th' honor of liberatin'

it."

Joe was created first by Mauldin, well before

Pearl Harbor. Joe was never an angel, but at least he was a cleanshaven, well-scrubbed

young man, and he appeared in various Army publications, especially the 45th

Division News. After 07 December 1941, he met Willie, and the two went through

the Italian campaign together, becoming disreputable in their personal habits.

During training Joe was a Choctaw Indian with

a hooked nose, and Willie was his rednecked straight man, As they matured overseas

during the stresses of shot, shell and K rations, and grew whiskers because

shaving water was scarce in mountain foxholes, for some reason Joe seemed to

become more of a Willie and Willie more of a Joe.

Willie and Joe and their creator made the cover

of Time magazine in 1945 — the year after Mauldin won his first Pulitzer

— and he came home from the war a celebrity. He had made a lot of money but

wasn't very happy. "I never quite could shake off the guilt feeling that I had

made something good out of the war," he said.

After the war, Mauldin seemed lost for a time.

He covered the Korean War briefly for Collier's but was not entirely

pleased with his work. He resuscitated Joe, made him a war correspondent and

had him writing letters to the stateside Willie. In 1958 he visited Dan Fitzpatrick,

editorial cartoonist for The St. Louis Post-Dispatch, who disclosed

that he was planning to retire. Mauldin applied for the job, got it and won

a second Pulitzer Prize in 1959 for a cartoon on the plight of the Russian author

Boris Pasternak. The cartoon showed two prisoners in Siberia,

one of whom said to the other: “I won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

What was your crime?”

Mauldin remained with The Post-Dispatch

until 1962, when he joined The Chicago Sun-Times. He seemed to regain

his old form and was regarded as one of the most influential cartoonists of

his day.

Besides segregationists, redbaiters and dictators,

Mauldin used his pen to strike at the Ku Klux Klan and veterans' organizations

that he thought were too far to the right. He later said he thought he had gone

too far in his denunciations and "became a bore." Many newspapers agreed and

began to drop his syndicated cartoons.

He became an advocate for veterans and joined

the American Veterans Committee, which saw itself as an alternative to more

traditional organizations like the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign

Wars. He served two terms as its president in the 1950's.

Mauldin did not confine his activities to drawing.

His postwar book Back Home was as much a job of writing as it was drawing,

and it received good reviews on both counts. He also appeared in two movies,

both made in 1951. One was John Huston's Red Badge of Courage, with

Audie Murphy, the most decorated hero of the war. Mauldin received good reviews,

but the movie failed at the box office. The other was Teresa, directed

by Fred Zinnemann.

In the middle 1950's he moved to Rockland County in New York, and in 1956 he

ran unsuccessfully for Congress against the incumbent in the 28th District,

a conservative Republican named Katharine St. George. Mauldin, a Democrat, thought

of himself as the left-of-center candidate.

In the middle 1950's he moved to Rockland County in New York, and in 1956 he

ran unsuccessfully for Congress against the incumbent in the 28th District,

a conservative Republican named Katharine St. George. Mauldin, a Democrat, thought

of himself as the left-of-center candidate.

Among Mauldin's other books are A Sort of

a Saga (1949) — Bill Mauldin's Army (1951) — Bill

Mauldin in Korea (1953) — What's Got Your Back Up (1961)

— I've Decided I Want My Seat Back (1965) — The Brass

Ring (1972). He also illustrated many articles for Life, The Saturday

Evening Post, Sports Illustrated and other publications.

William Henry Mauldin was born on 29 October 1921,

in Mountain Park NM, one of two sons born to Sidney Albert Mauldin, a handyman,

and Edith Katrina Bemis Mauldin. As a child, he suffered from rickets, a disease

caused by a deficiency of vitamin D, and was unable to engage in strenuous activity.

His head seemed too big for his spindly body. When he was 8 he heard one of

his father's friends say, "If that was my son, I'd drown him."

Mauldin never forgot the insult and turned all

his energy to teaching himself how to draw. His family moved to Phoenix, and

while he was still in high school there he enrolled in a correspondence cartoon

school. He left high school without getting a diploma, moved to Chicago and

continued his studies at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. His maternal grandmother

gave him the $300 tuition fee.

He moved back to Phoenix and began to sell his

drawings. Some of the first were published by Arizona Highways magazine.

In 1940 Mauldin also created cartoons for both sides in the Texas gubernatorial

campaign. He later said he joined the Arizona National Guard to avoid the Texas

politicians, who discovered he was working both sides of the fence. The Guard

required no physical examination — Mauldin doubted he could ever pass one —

and he was accepted. When the Arizona Guard was federalized in 1940, Mauldin

found himself in the Army.

He scored more than 140 on his Army I.Q. test

and later said that once the Army became aware of this, it did with him what

it tended to do with all bright people who become enlisted men: it gave him

K.P. for four months. He managed to get a transfer to Oklahoma's 45th Division

so that he could draw cartoons for the 45th Division News, first as a volunteer,

later as a member of the staff.

Mauldin married Norma Jean Humphries in 1942.

They were divorced in 1946. The following year he married Natalie Sarah Evans,

who died in a car accident. In 1972 he married Christine Lund. His survivors

also include his seven sons; a daughter died in 2001.

Mauldin had two war experiences after Korea.

One came in 1965 when he visited his son, Bruce, a serviceman stationed in Vietnam.

Mauldin wrote about an attack on Pleiku. He also visited troops in Saudi Arabia

during the Persian Gulf war in 1991, toward the end of his career. He did not

approve of the war, and his cartoons were especially hard on President George

Bush. He made no further use of Willie and Joe.

In 2002 Mauldin's health and memory declined

in a nursing home in Orange County, California.

In the middle 1950's he moved to Rockland County in New York, and in 1956 he

ran unsuccessfully for Congress against the incumbent in the 28th District,

a conservative Republican named Katharine St. George. Mauldin, a Democrat, thought

of himself as the left-of-center candidate.

In the middle 1950's he moved to Rockland County in New York, and in 1956 he

ran unsuccessfully for Congress against the incumbent in the 28th District,

a conservative Republican named Katharine St. George. Mauldin, a Democrat, thought

of himself as the left-of-center candidate.